Similar to Willie Varela’s style of experimentation in film, like his e-mail article “Remembering Stan Brakhage: An E-mail Conversation between Steve Anker and Willie Varela,” that he and Anker co-authored in Spring/Summer 2005 issue of the Journal of Film and Video, I invited Varela’s long time friend Robb Chávez to be part of the interview. Robb could not be present at the interview, but he e-mailed me his questions that I used. Varela is a pioneer and internationally known El Paso Chicano artist in an avant-garde field that is very exclusive. Chávez recalls Varela making numerous Super 8 films beginning the summer of 1971 (when he showed his very first effort in his house, to his family and Chávez was there). Chávez states that looking back Varela may see those early films as sort of like training or rehearsals, but at the time, he wanted everybody to think of them as completed works. Chávez said that some of Varela’s early films might have appeared amateurish and that he might have been reluctant to acknowledge them as part of his overall “oeuvre” in this interview, but his early films demonstrated his growth, aspirations and struggle to be recognized as an underground filmmaker. Chávez said that in the 1980s Varela was a protégé and cultural disciple of Stan Brakhage until Brakhage’s death in 2003. He was also friends with Brakhage’s then-wife Jane. Brakhage was a world-class artist, the pioneer of post-war experimental film. He made hundreds of films for 50 years, from the early 50s to his 2003 death. Brakhage was larger than life, the Orson Welles of “personal film.” Brakhage was not only a filmmaker, but he was also a film theorist. According to Chávez, the first film Varela made was a comedy with cartoon music from old cartoon, “Top Cat.” Varela’s work came to fruition during the Chicano Movement when Chicano activists thought film should be documentary & narrowly political. For a Chicano filmmaker to produce underground films during this period was ground-breaking.

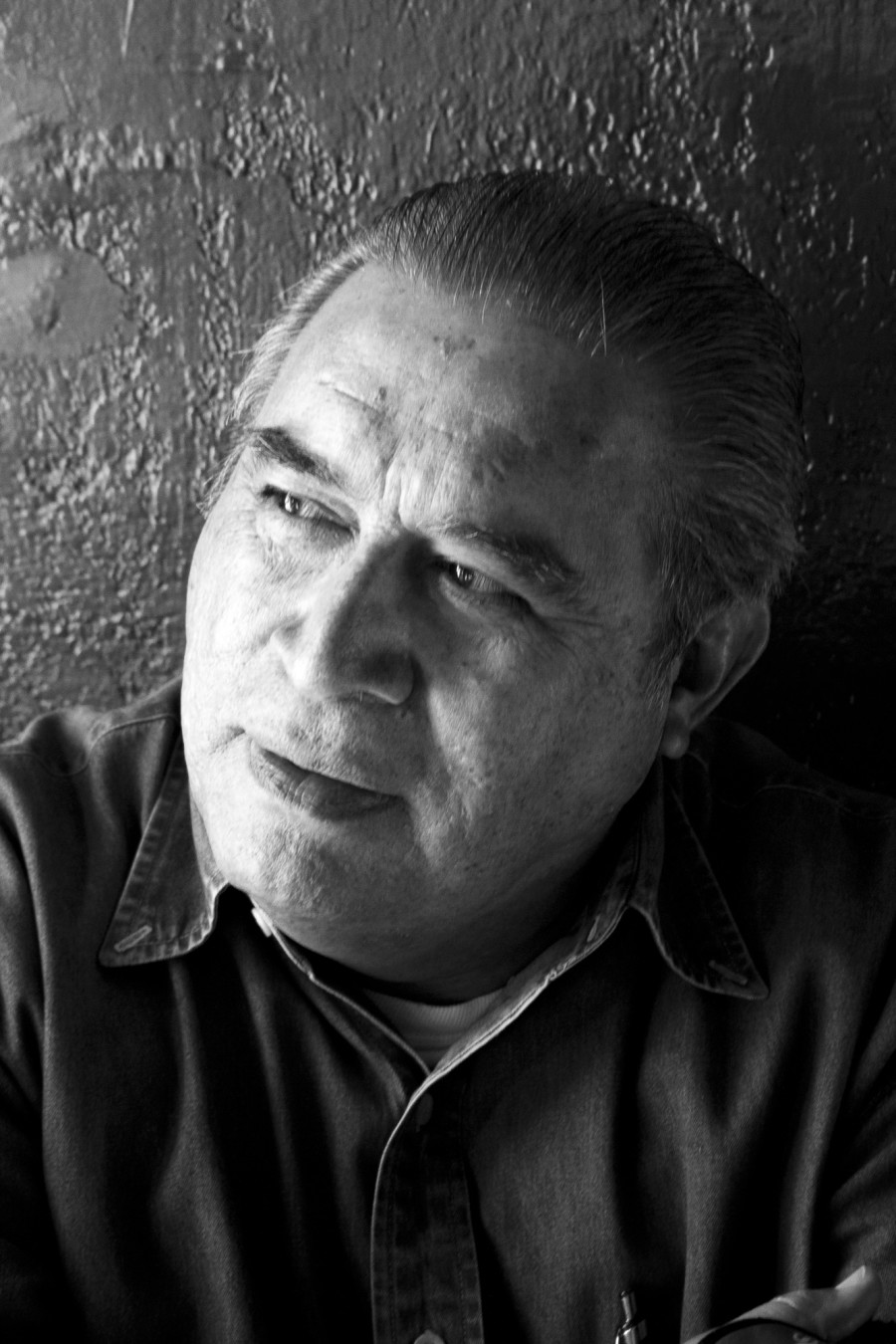

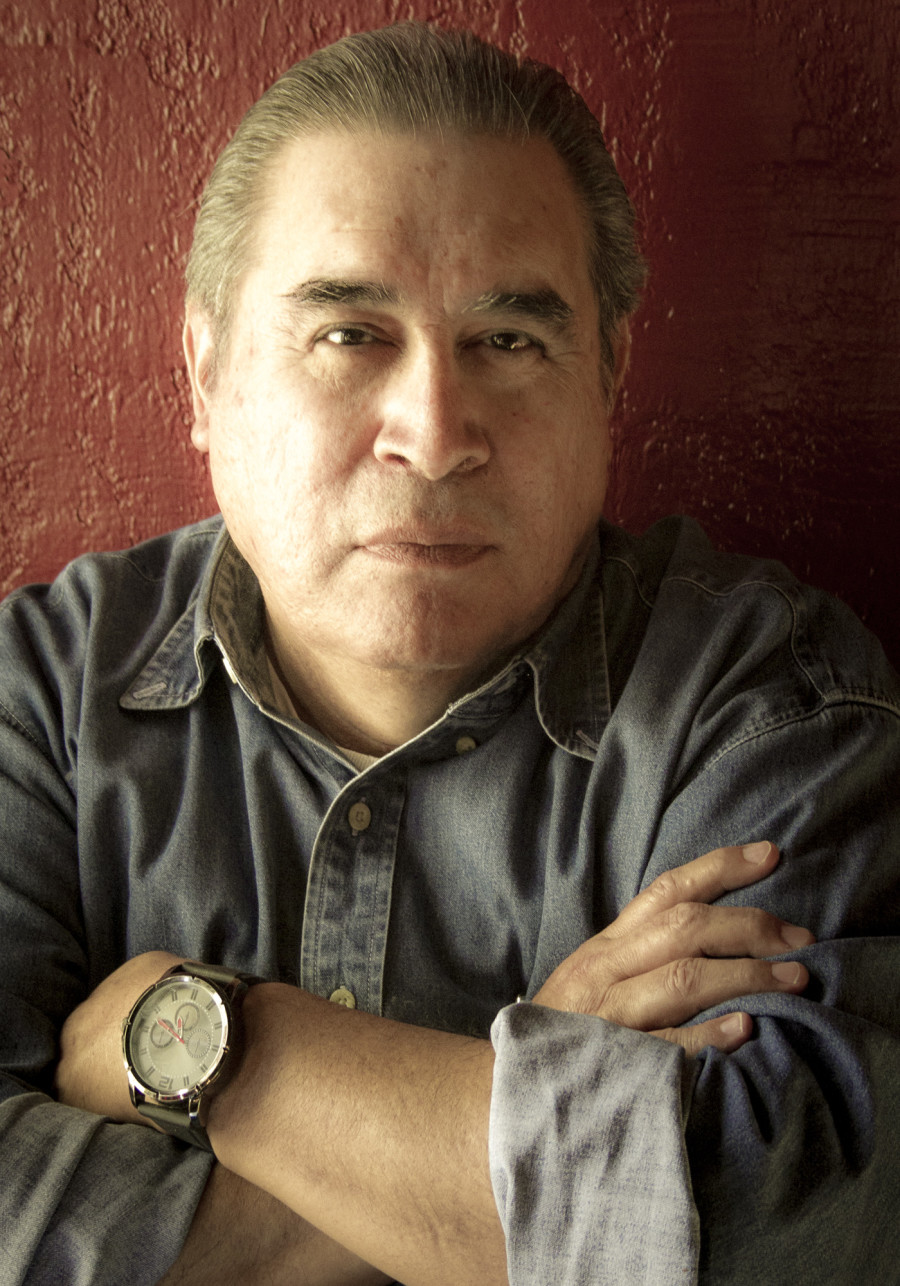

Miguel Juárez: Today is Monday, May 30, 2016. My name is Miguel Juárez and I am interviewing filmmaker Willie Varela, in El Paso, Texas. Willie, thank you for agreeing to do this interview. Willie, first off, can you tell me where you were born and raised and where you attended school?

Willie Varela: I was born in El Paso, in 1950, here in Texas, right in the middle of the 20th Century, during a period when it was regarded as a very boring period, with Eisenhower and all those things, but there were a lot of interesting things going on in the arts. The 1950’s saw the burgeoning of Rock and Roll in American society with Elvis Presley, with Little Richard and a lot of other people. There was already an underground film movement in the United States. People like Bruce Connor, Stan Brakage…

MJ: How did you hear about his underground movement? Didn’t you attend Catholic school?

WV: I went to Jesuit High School. Actually, I didn’t learn anything about the underground movement until the late 1960s when there was a lot of cultural and social ferment going on in the United States, of course, you wouldn’t have known it in El Paso. El Paso was still pretty insulated by all of that. I learned about the Underground by going to a bookstore that is now defunct but that was well known as the time called the Bassett Center Bookstore at Bassett Center. They carried a wide array of books on film and video. That’s where I bought my first copy of Robert Frank’s The Americans and I also bought a book called An Introduction to the American Underground Film by Sheldon Renan. The book had the whole history of the avant-garde that went all the way back to the beginning of film. It went back to the beginnings of film at the end of the 19th Century with the Lumière brothers and then films that were then made in France in the 1930s by Man Ray and Marcel Duchamp. Of course, there were films like Fantômas (1913-14) and the Vampires made by French filmmaker named Louis Feuillade. There were lots of things going on and the 1950s in the U.S. there were things happening but they were happening underneath all the political turmoil at that time. Don’t forget, during that time, there were the McCarthy Hearings where Senator Joe McCarthy was seeing a communist behind every bed and every artist in Hollywood and every screenwriter and every actor in Hollywood was suspect. And then you had people like Ronald Reagan and Adolph Menjou and Elia Kazan who all snitched about their colleagues who they suspected about being communists.

MJ: How did you go from reading about underground film, or avant-garde or experimental film to thinking of doing it and actually doing it?

WV: Well, I will tell you what happened and this is an interesting story. I read about Brakhage and in this book An Introduction to the American Underground Film. They had a lengthy biography on Stan.

I had no guidance. I was here in the middle of nowhere with no one to take me aside and say “This stuff is terrible or go in this direction or try this or try that.” It took me a good five years of just shooting things and trying to conceptualize in my mind what would make an interesting film.

MJ: And Stan Brakhage was?

WV: Stan Brakhage was probably one of the great artistic geniuses of the 20th Century, who died in 2003. He was only 70-years-old but I got to know him a little bit over the years before he died. At the time I was only 19 or 20-years-old and I read in this profile that among all the 16 mm films that he was making like epics like Dog Star Man (1961-64) and Scenes from Under Childhood (1967-70) and all these other great works that he had been making a long series of films in eight millimeter. Eight millimeter was the traditional home medium that none took seriously. Eight millimeter was strictly supposed to be about home movies. It wasn’t supposed to be a vehicle for artistic expression. The mayor reason he came to 8 mm film was because he had been showing his films in New York and apparently he had driven to up to New York and he has his 16 mm equipment stolen, so he cashed in his insurance on the equipment he had and all he could afford was 8 mm equipment. And from there, he made a series of films called The Songs (1964-69). He made well over 26 of them. A couple of them very lengthy ones, one very long and intense meditation on the Vietnam War called The 23rd Psalm Branch (1966-67) and a series of portrait films about his friends and colleagues in the movement, and I thought to myself, wow, these are just 8 mm films. They are home movies. You could get the cameras anywhere. The film was cheap.

I started thinking about that because I was very much at loose ends in my life. I had flunked in and out of UTEP a couple of times. During the draft, I waited uneasily from aged 18-21, hoping not to be selected during this period. I didn’t have a job. I didn’t have a girlfriend. I was truly a loser, but also kind of an invisible man in American society. So that was one thing that started me thinking that this was something that I could get into that would justify my existence. But then I read in a very lengthy interview that was conducted by Jann Wenner who was then and still is the editor and publisher of Rolling Stone Magazine. He had a very lengthy interview with John Lennon and Yoko Ono. And Lennon, of course by 1970, 1971, he was one of the first band members to leave the Beatles. He was living in a tiny basement apartment in Manhattan with Yoko Ono and doing all kinds of things he had never done. He always considered himself just a rock musician “Beatle John” and that was it. But Yoko Ono, who had her own career as an avant-garde artist introduced Lennon to new ways of thinking art—installation art, new ideas in painting, in sculpture, happenings, all that sort of things. So Lennon also bought an 8 mm camera and started making films. So there was this guy Brakhage who lived in the mountains of Colorado because he lived in Boulder at that time; he was very isolated, but he was establishing a very powerful and significant reputation outside of that area and then John Lennon who had already been a member of Rock and Roll group that transformed the world. These two guys were making 8 mm films and I thought, “Well hell, if they are doing it, why can’t I do it,” because it was within my means.

MJ: What was the first film that you made; and you have over 100 films that you have produced to date?

WV: At least that and probably another 30-40 videotapes, and many, many photographs and installations and all of that.

MJ: Now, I want to get into one of Robb Chavez’s questions. Robb, one of your longtime friends asked me to ask you: What does it mean to be a highly creative artist, living a super-ordinary life in El Paso?

WV: Well, I will tell you, it’s very boring, most of the time. As Brakhage called it, he called it “living life on the limited shelf.” Brakhage came to El Paso. I brought him to El Paso like three or four times via the auspices of UTEP a couple of times. One time I wrote a grant to bring him specifically to visit El Paso, so he got to see a little bit of the city. It was obvious to him that El Paso, even though it was big geographically, that there was a lot of land, it’s expansive and all of that, that there was nothing going on here. And he was right, there wasn’t anything going on here, even now in 2016. I’m an artist who is already passed middle age. Some people would call it my declining years. I hope I am not declining too much. I am 66 now and I can tell you that living in a place like El Paso is very boring. I find it very boring and very frustrating and not very challenging but that has created for me a whole new project in my mind and in my consciousness. My cognitive abilities have grown in a sense because of the nothingness of El Paso.

MJ: I would disagree with you. There is really a lot going on here. There are a lot of younger artists who are producing important work.

WV: You are not allowed to disagree with me; you are supposed to be interviewing me! (Laughs)

I was after trying to do something that was challenging; that was beautiful and sometimes not so beautiful. Beauty in itself is not an end. It’s part of art.

MJ: …doing performance art, etc. Given that you feel that nothing is going on in El Paso, next, I would like to speak about art making. There was about a ten-year period when you did not produce work. There is a whole generation of artists who do not know your work. You are not on social media. You’ve told me in a previous conversation that you are producing new work. So my next question is two-fold, what kinds of works are you producing and how do you stay relevant in the art world?

WV: I agree with you. I am always interested in what young people are doing. I was a professor of film studies at UTEP for nine years in the late 1990s and 2006 before I was kicked out of academia. I got to see a lot of the work that they were doing. So I got to see good work, some promising work, some terrible work. It varied from person, to person, to person. The thing that impressed me was that when they were taking me, I would give them guidance. I would give them my opinions on their work and I myself didn’t have that guidance. I bought my first camera in 1971. I bought a Vivitar Super 8 Silent camera and I also bought a Minolta 35 mm camera because I wanted to do both. I wanted to be like Robert Frank who did both. He shot still photographs and he made films. I had no guidance. I was here in the middle of nowhere with no one to take me aside and say “This stuff is terrible or go in this direction or try this or try that.” It took me a good five years of just shooting things and trying to conceptualize in my mind what would make an interesting film? One of the first films I made that received notice was one called Green Light (1976). Not necessarily just an avant-garde film, but something personal, something watchable. It was a film that was made with a roll of Super 8 film that I bought at Kmart. At that time, Kmart was actually manufacturing film and this particular roll was out-of-date. I bought it for .50 cents. With this roll, I made a short, two-and-half minute film, but it was the first film that attracted some attention.

MJ: A follow-up question regarding the technical aspects of film and filmmaking, when do you know that a film is finished?

WV: I think that you know when a film is finished when the aesthetic of the film, the area that you working with, what you are trying to say, whether it’s a more meditative study on something, whether it’s political oriented film, whether it’s a portrait of somebody, whether it’s a found footage piece, you know when the film is finished is when it feels like a whole. When it’s a whole. When you feel that you have everything in there that you need to have, so that’s how you know that it’s the end of the film. Sometimes it can be very short. It can be just a few minutes, three, four, five minutes. Other times, the really long film that I made was titled Making Choosing, the Fragmented Life, a Series of Observations. It was a Super 8 sound film and it was 102 minutes and that’s a long film and it was the longest film that I have ever made. That film had to be that long in order to encompass all the things that I was trying to say about marriage, about being a new father, and tension in my relationship with my then wife, etc., etc.

MJ: We were speaking before the previous question about staying relevant in the art world, here’s another Robb Chávez question that addresses part of that issue: El Paso has a long tradition of “Everyman artists,” self-made creatives who have pursued their art for decades–not because they went to art school, but because their inner selves demanded that they make art or that they write, artists and writers such as John Rechy, F. Murray Abraham, Ricardo Sánchez, and Luis Jiménez Jr. What inspired you by this tradition of what Chávez refers to as self-made artists?

WV: Another word for that is an autodidact. It sounds like a disease or something like that but it means self-taught. I was the kind of guy that even though I never took any art classes, etc. I have a very deep interest, for example, in popular music. I was the kind of guy who would buy a record and if there were liner notes or anything like that I would actually read them. I would actually sit down and I would read them. If the lyrics were printed on the sleeve of the record, I’d read them. If there was something I wanted to know about, like the Beatles; I will use them as an example. If there was a book or magazine that gave special insight to the Beatles, I would buy it and read it. So little by little I taught myself about contemporary music. I taught myself about art, especially modern art, abstract art, pop art. I taught myself about photography, by buying photograph book and then eventually photographing myself. I learned about installation art again by buying books and seeing my very first installation at the Whitney Museum of American Art in New York in 1981 when I saw an installation by Puerto Rican artist named Frances Torres. I came to have a very eclectic view on the arts but I was especially interested in film and photography.

MJ: How would you explain your films and style of filmmaking to someone in El Paso who has never seen your work? Robb asks how do you interact with an environment that may not very responsive to your work?

WV: Well, if I were trying to tell somebody what my work is like, I think I would say that, maybe just for expediency sake, I may say “Oh, it’s a little bit like music videos.” That’s something that everyone knows a little bit about. I would say that maybe they were filmic montage studies, about one thing or another. They were not meant to be commercial. They were not meant to be shown in big theaters and make a lot of money. I had no interest then (although I have more interest now), I did not have any interest in Hollywood, nothing really serious, although I knew a lot about Hollywood. I had a handful of actors whom I liked as personalities. I would say that I could tell someone about how to approaching my films would be to just open yourself to the experience, not be judgmental, not be critical, until the experience is over. Then you could come and say: “I really didn’t get this; I really didn’t get that; I didn’t like this part; I didn’t like that part,” then I could address that. What was the other part of your question?

MJ: Have people asked you why you pursue the creation of avant-garde film versus popular films. Wouldn’t popular films have more appeal?

WV: Well, of course it would. Even someone like Brakhage it probably took him a lifetime to have the same number of people see his films as the first people who saw the first two or three Star Wars. It took years and years but the difference is that those films may be entertaining and people nowadays self-identify so strongly with these characters that it gets to be kind of ridiculous and you wonder if they are surrendering their identities to throw themselves so much into the lives of these characters? I was not after that. I was after trying to do something that was challenging; that was beautiful and sometimes not so beautiful. Beauty in itself is not an end. It’s part of art. Look at the work of Jackson Pollock. I don’t think anyone could have said that his work was beautiful, but it was certainly challenging. I persist in making this kind of work because that’s my temperament, that’s my nature, that’s my consciousness, that’s what I find interesting. I see very little out in the world, whether it’s the outer world that we know or even our inner world. All of us are to a certain extent in turmoil. We are all trying to get a handle on our interior lives. We are all trying to make some sense out of our fellow human beings. At the time of this interview, we are dealing with one of the most serious threats to democracy in the presidency with Donald Trump. And god knows what is going to happen with that and god help us if he is elected president at this time.

My credo was that if an artist is not free to do what he or she wants to do, then no one is free?

MJ: Shifting the discussion now, where are some of the film showcases where your work has presented or shown?

WV: Oh gosh, I have resume with dozens and dozens of film places of showcases where I have had one-person shows. I started my exhibition life in 1979 when Carmen Vigil, who at that time was the director of the Cinematheque in San Francisco, he gave me my first chance. I sent him some of my films. He had a chance to look at them and he decided that I was a new voice that he should give him a little row to, give him a chance, give him an opportunity to put the work out and see what happens and that’s how it started. Since then, I have shown at the Cinematheque several times. I’ve shown at the Pacific Film Archive, at UC Berkeley. I have shown at the Museum of Modern Art. I had a Cineprobe (a film series at MOMA in New York City) there, a one-person show in 1988. I have been in two Whitney Biennials (at the Whitney Museum of American Art in New York City), in 1993 and 1995. I had a full retrospective that was curated by Dr. Chon Noriega (Film Professor at UCLA) at the Whitney in 1994. I have had various articles published in magazines and books.

MJ: I wanted to ask you about the Chicano Movement in relation to you and your work. The Movimiento/Movement came and went and some would claim we are still living in it but your work doesn’t seem to address issues within the Chicano Movement? At the same time, the Chicano Movement may have opened opportunities for artists like you to be accepted.

WV: I never knew that the Chicano Movement did anything for me, to tell you the truth. I have to be honest. I was very aware of the Chicano Movement. I was aware of El Teatro de los Campesinos, Cesar Chávez. Later on, it was Guillermo Gomez-Peña. I got to know him and see a lot of his work. I knew about Culture Clash, who were certainly more inline with my generational values with Richard Montoya and those guys. I would say that I did make films that were tangentially about the Chicano Movement. They may have not been directly about the Chicano Movement. For example, I am a severely lapsed Catholic. Over the years, I have made a series of films shot in various cemeteries here in the Southwest in El Paso, as well as Los Angeles, shooting in Forest Lawn and trying to understand these rather strange, symbolic representations of god with the dead buried underneath these things. My films very much had, I think, a Chicano viewpoint to them. I didn’t come from a privileged background. I was not privileged in terms of my equipment or the money I had to expensive films or for travel. I had to fight for every single screening. Some good people took chances on me but I have to say that some of the worst presentation and receptions that I got were at Chicano institutions. They either saw me as a Gringo sellout or they saw me as a pseudo-Chicano or “You say that this is so good, why aren’t there any pictures of the Guadalupe in them and so on and so on?” My credo was that if an artist is not free then who is free? My credo was that if an artist is not free to do what he or she wants to do, then no one is free? That’s the way I took it. Now, of course, I am getting a fair amount of attention.

MJ: Your comments lead me to my next question, Dr. Scott Baugh from the Department of English at Texas Tech University, who focuses on film studies, is currently working on a retrospective book on you and your work, can you tell us a little about that project? How did you meet Scott?

WV: That is a project that is long in coming. It has been in the works now for three, possibly four years. We have been trying to get everything together and trying to develop a viewpoint, because after all I have just been a regular working kind of guy. Sliding in and out of the middle class. One year I may enough money to be middle class and other times I am barely above the poverty level. I have an archive of my films, videotapes and photographs that need to be organized but I approached Dr. Noriega a couple of years ago about taking a lot of films and videos and putting them in their archives so that they would survive because they were just in boxes in my house. As you know, film deteriorates, videotapes deteriorates, especially film if it is not kept at a certain temperature and they were very happy to take my work. Now the question remains are they going to do anything about preserving that work? I would say that for the first time now in the latter stages of my life, in the latter stages of my career, now there are sufficient numbers of Chicanos, of minority artists of all stripes who are very open to everything. Just because you are Black, doesn’t mean you have to make Black art. You can make with other kinds of people and create something that is important to you. Chicanos nowadays don’t have to have a portrait of the Virgen in every single picture they take. I think things are opening up but it is only because there’s so much to choose from and artists are realizing that they are free, like I said, they are free. And if you happen to be a certain type of artist, like a Jasper Johns or Robert Rauschenberg when they were alive, you were held by a contract by the gallery. They were held by contract by the gallery that represented them and made them wealthy men and in their contracts for ten years they had to promise that there would be no serious change of style in their work because the whole point was to sell paintings. Guys like Brakhage, Bruce Conner and Kenneth Anger and all those; they didn’t operate under those conditions. They made whatever they wanted to make, damn the torpedos!

I photograph the areas that have visual and/or social and political interest because they are so neglected, so forgotten, so nothing.

MJ: Robb wanted me to ask you, you’re also an accomplished photographer. Do you approach photography differently than your moving image work?

WV: Yes, I do. I usually do. My current project in El Paso that I started a few weeks ago consists of instant photographs. I bought a Fuji Instax Pics camera and my project now is to photograph the detritus of El Paso, the nothingness of El Paso. I photograph the areas that have visual and/or social and political interest because they are so neglected, so forgotten, so nothing.

MJ: What’s an example of nothing El Paso?

WV: For the very first time, I decided I had four packs of film, ten photographs in each. I took all of them out in a couple of weekends and I went onto Dyer Street. You go onto Dyer and Dyer is one of the most colorful but also very run-down areas and neglected and it is not a place where people would for example take tourists to, and that’s exactly what I am interested in. I shot some photographs of some weird murals that are out there. I’m interested in the fact that El Paso is probably like any other major American city in that it has a lot of things that cross time barriers. Things are left over from the fifties or sixties or seventies and they have all gone to seed. Nobody cares about them anymore and those are interesting to me because things that are modern, that are brand new, they are all designed to project a certain image, of a community, of an environment. Many times they are not very interesting architecturally or otherwise. That’s why I have started seeking out the detritus of El Paso. I live here and granted I get very bored, very frustrated but where else are we going to go? You can go to San Francisco, where I lived for three years in the early 1980s, but San Francisco is now the most expensive city in the United States to live in. It is now more expensive than Manhattan. If you tried to move to Manhattan or any area around the New York area, it would be hard to create anything because all your money would have to go to pay rent and food.

MJ: Robb asks what is a reoccurring theme that you try to convey in your artistry as a whole?

WV: What I try to do is to point or to guide people’s eyes to think to things that they hadn’t noticed before. What might appear to be the ordinary, this is what I mean by the detritus of El Paso. People go all the way to Greece and Rome to see ruins. They don’t go to see the Coliseum beautifully built up or the Acropolis. They go there to see the ruins of these places. I’m interested in kind of finding out the ruins of a place like El Paso and showing that there is beauty in these things in a strange way. It is not something that is going to be beautiful like say like the Luxor or the Venetian in Las Vegas, even though these are very commercialized, there are still very beautiful architectural spaces. I am not saying that all of Las Vegas is beautiful but Las Vegas has created its own world. It’s a world on the strip.

MJ: Robb asks where does your work fit in film history?

WV: I would say that my work fits in film history…I might be tempted to say in small way but not necessarily because it is just like a small photograph. How do we know that that photograph couldn’t be influential to generations? Does it have to blown up to forty by fifty feet? Does it have to be a giant mural under the freeways in Los Angeles like that great fantastic mural of Ed Ruscha? I’m saying that all endeavors, whether they are small or large seemingly have impact. You never know what is going to shake out of all this stuff? You just never know, just look at music. Even when contemporary music was being sold in vinyl you only had a nine by twelve inch sleeve, hopefully a nice picture on the cardboard and notes on the back and you had a round black disk. It wasn’t the Trump Towers or the Sears Building but the music that was contained in that is what changed the world. Like the Beetles and David Bowie changed the world and the Rolling Stones and Brian Eno and all of these people. They changed the world and people may not always be aware of it, but they did. Certainly, a guy like Andy Warhol, whom I have studied extensively and love his work. All you have to do is look around you in any big city and Warhol is everywhere.

My reason for living was to make this work. To make something beautiful, interesting, challenging, that in a sense, if I were to say something grandiose, it would be to help my fellow man and woman to grow, because in the process of making those things, I have grown too.

MJ: My last question, where is your work archived and you have answered part of it. Where can people see your work? Where can people order copies of your work? What would you like people to remember about you or your work?

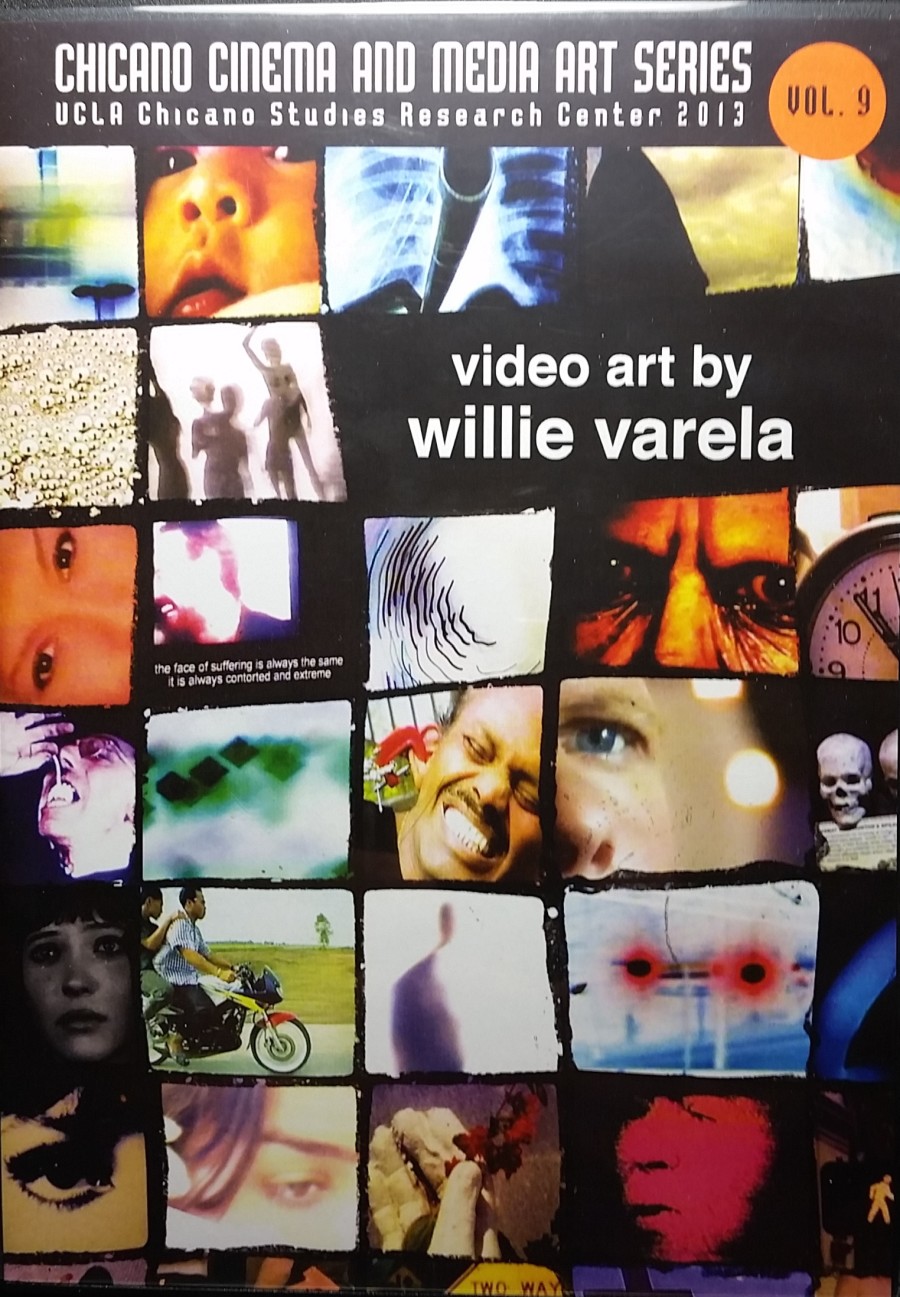

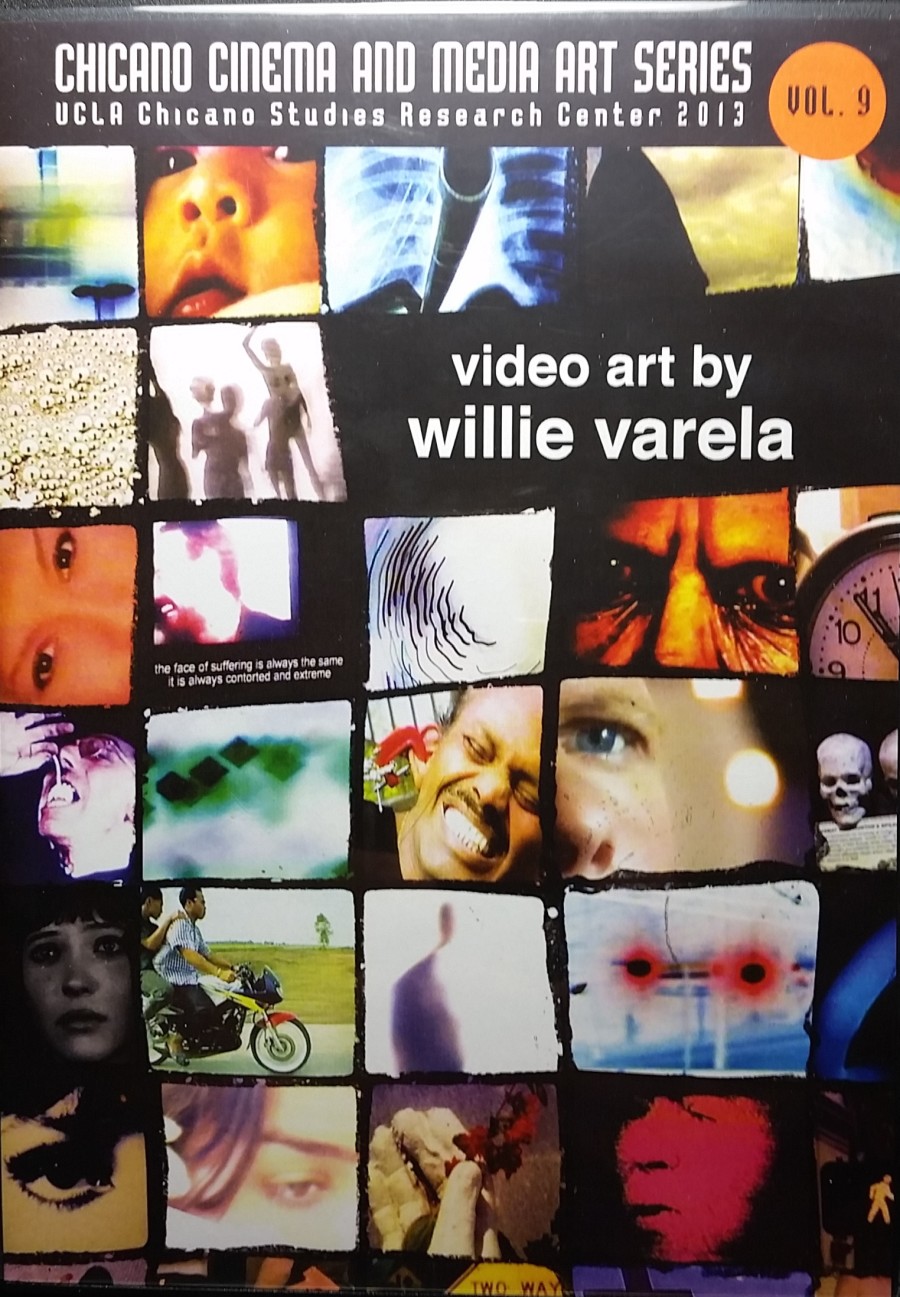

WV: Most of my work, not all of it, I have to send the remainder of my films to the UCLA Chicano Studies Research Center Archives. Chon told me that they are currently being housing in the Television Academy of Arts and Sciences in the vault out there that is pretty fancy. They have a temperature-controlled vault—that’s where that stuff needs to be. If people want to see my work, the best thing to do is for people to purchase my DVD, Volume I that is called Video Art by Willie Varela and it’s published by the UCLA Chicano Studies Research Center. All they have to do is visit the site at: http://www.chicano.ucla.edu/publications/dvds. People can purchase a DVD that has over 400 minutes of my work in Super 8 and video. It gives you a broad overview of what I have done. What was the other question?

MJ: What would you like people to remember about you or your work?

WV: I guess if I was to be remembered and I mean this in a humanistic and a very secular way is that I tried to go beyond my station. I didn’t just settle for being a namby-pamby Chicano living in El Paso. I didn’t pour $40,000 in a ranfla (an automobile). I spent a lot of my money and time making art that was designed to try and bring some beauty to the world. That would really about it. I think that’s a pretty damned good reason for living, because many of us go around thinking what am I here for? What am I supposed to do? What is the purpose of this life? A very good friend of mine George Kuchar, who was an underground film director, who died in 2011 made this really beautiful film titled A Reason to Live (1976). I think we all think about that. We all think about what is my reason for living? My reason for living was to make this work. To make something beautiful, interesting, challenging, that in a sense, if I were to say something grandiose, it would be to help my fellow man and woman to grow, because in the process of making those things, I have grown too.

MJ: Okay, that’s it. Thank you.

Miguel Juárez is doctoral candidate (ABD) in history at the University of Texas at El Paso and is the author of Colors on Desert Walls the Murals of El Paso (1997, Texas Western Press) and is co-editor (with Rebecca Hankins, Associate Professor at Texas A&M) of Where Are All the Librarians of Color: the Experiences of People of Color in Academia (2015, Library Juice Press). His research interests include libraries and archives, artists and art making, borderlands history, Chicana/o history, culture and urban and planning history. You can follow him @miguelJuárez

Robb Chavez is a freelance writer and political activist. His major emphasis is on party politics, urbanism, & the influence of media on socio-cultural issues. He is also very interested in Southwest urban history. Chavez is a 3rd-generation El Pasoan & currently resides in Albuquerque. He can be followed @robb_chavez, but his main social outpost is on Facebook.

Text: Miguel Juárez | Photos: Ted Carrasco, Miguel Juárez & Artpace San Antonio