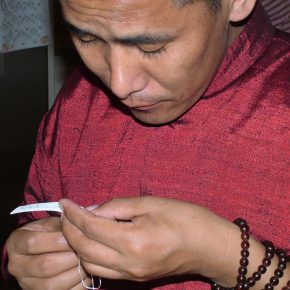

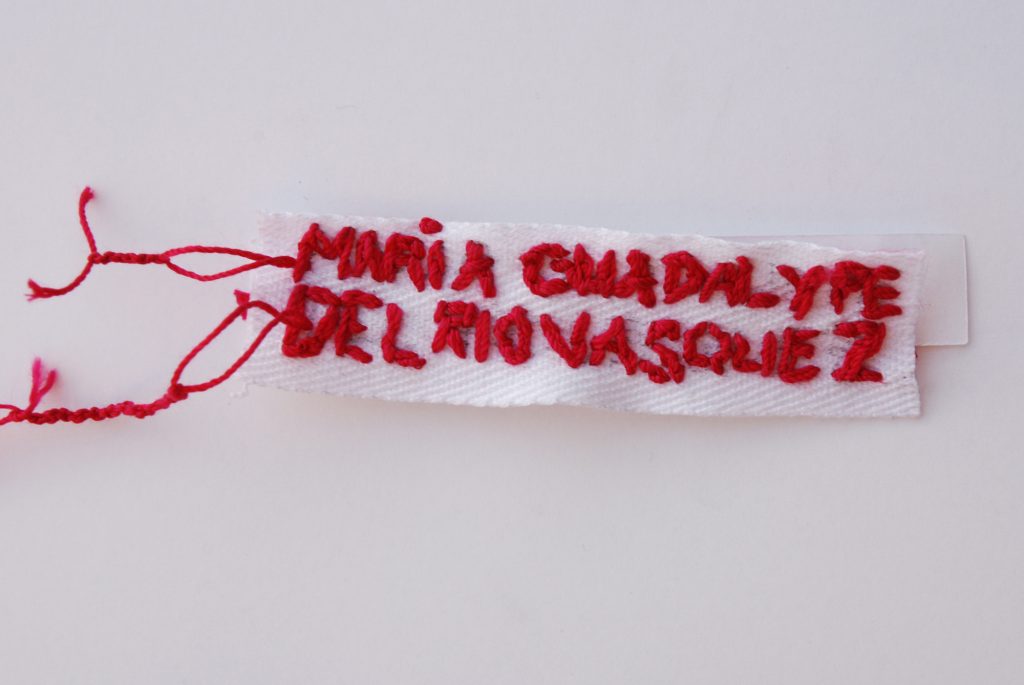

Art has the power to cross and interconnect borders, lives and memories. Oslo-based artist Lise Bjorne Linnert with Harald Gunnar Paalgard, cinematographer from Dramatiska Institutet in Stockholm, Sweden and Marcela Descalzi, a Houston based educator and translator, are visiting the El Paso Juárez border and México City to extend the reach of the Desconocida Unknown Ukjent project. The project was initiated in 2006 at a group show in Houston titled Frontera450+ where Lise was invited to make work about the Juárez femicides alongside artists such as Luis Jimenez and Margarita Cabrera. She developed her final concept of having workshops where communities come together to embroider the names of women affected by violence in Juárez and using the word “Unknown” that symbolizes the people affected by violence everywhere with colorful silk and textiles. These objects created serve as a participatory awareness activity and “silent protest” against violence everywhere.

Miguel: Lise, can you tell us how you developed Desconocida Unknown Ukjent project?

Lise: In 2006, the Station Museum of Contemporary Art in Houston had an exhibition called “Frontera 450+.” It was dedicated to the women of Cd. Juárez and they invited me to contribute with a project. I had lived in Houston, but by then I had moved back to Norway. My first reaction was that I felt so distant to the situation and I asked myself “What can I do?” I wanted to spread awareness of what was really going on, but to do it in a way that would connect without separating into “an us and a them.” After research and consideration, I decided to invite people to embroider the names of the murdered women in Cd. Juárez. I also wanted everyone to embroider an “unknown” in their own language to memorialize individuals in their own society, who were exposed to similar violence, but whose names we didn’t know. The list of names from Cd. Juárez is incomplete, so in many ways, the unknown label stands for both, the “unknowns” in Juárez and the unidentified victims in rest of the world. I wanted the workshops to take place in many different countries. I sent out materials with instructions in envelopes. Soon it developed a life of its own. Because the situation in Juárez didn’t get better, the project continued to grow, and it is still going on today.

Nicolas: Harald, you are an accomplished Norwegian cinematographer. Are you documenting the project? If so, what can you tell us about your experiences documenting Desconocida or traveling with Lise on this journey?

Harald: Yes, in my own way. It’s my way of seeing it.

Lise: Harald is part of it; he is not making a documentary.

Miguel: So, it’s his artistic vision of the project?

Harald: Yes, it´s my vision of the situation, the place and the meetings.

Miguel: Lise, you include embroidered nametags of other women in other countries, what countries specifically are included in the project? And you mentioned earlier that you had about 7,900 names?

Lise: I think the workshops have been to almost all corners of the world except to the African continent. It’s been to Asia: Japan, Indonesia, Nepal, the Philippines and China. It has been to many countries in Europe, including many places in Norway, Sweden and Denmark. In the instructions for the workshop, I ask a leader to invite people to sew together as a group. The group can have as few as two participants or it can include all the students in a small university. I’ve lost count of how many workshops have taken place, maybe 500? Out of all the envelopes I have sent, there is only one that was not sent back.

Miguel: To clarify, these are workshops where you send out the materials with instructions on how to create the embroidered nametags and then they send them back to you?

Lise: Yes, I also encourage documentation of their gatherings and they often add poetry, photographs and other responses. When I exhibit the project, I always invite the local community to participate embroidering the last names added to the list of victims, and also ask their help to install the labels. Many participants come back to look for the names they embroidered.

Miguel: It’s like the Vietnam Memorial Wall where people come and touch the wall.

Lise: Yes, you could say it is similar. Because it has been going on for so long, there are many embroidered names and unknown labels. The wall of names began in Cd. Juárez but has grown to become an international memorial. I also see the act of embroidering as a form of protest, a quiet protest but a protest nonetheless.

Miguel: Specifically, who attends these workshops? Do men attend? If you have documentation that men attended, how is it different from a workshop when only women attended?

Lise: These are interesting questions. It’s democratic and open to all. You don’t have to know anything about sewing or embroidery because you receive simple instructions. It’s about the time you give and what happens when you spend that time with that name hearing that story. This is the essence and you will see from the embroidered labels that some of them are done very elaborately and some with more struggle, showing many knots on the back.

Miguel: So the stories are also included, or the biographies of some of the women are included?

Lise: Yes, but if I can, I also show Lourdes Portillo’s film Señorita Extraviada/Missing Young Women (2001). I have been in contact with her and believe the film speaks accurately of what’s going on. Although it was made in 2001, the only difference is that the number of victims are much higher today.

You asked me about the men. Although, it is challenging to get men to participate, they do in small numbers, unless the workshop is in a school, then boys and girls participate equally. I sometimes feel that men may feel as if they are being accused. In the UK, in a town named Chichester, a lot of men came to the workshops and I had to ask why. They answered it was because historically British men would embroider, which made it a natural thing for them to do. Perhaps to get more men involved I should have chosen an activity other than embroidery? Whether men are involved or not, the conversations in the workshops are similar. The act of embroidering does something to you, when you speak you speak more intimately.

Many names on the list have been embroidered several times but by different people. This connects to the Catholic belief that when you say names over and over, it is a way of honoring them. I really wanted to find a project that would raise awareness of the violence and the brutality, without celebrating them. The labels are made with silk threads in a rich variety of colors, involving thousands of hands, to bring life to the memory of the women. In contrast to memorials made of stone, embroidered names on the cloth-strips with hanging threads, are soft and alive.

Miguel: There’s a word in Spanish called “presente.” When you evoke someone’s name you state, so and so, presente, that they are present in spirit.

Nicolas: I think you touched on this but can you speak about how the tactile, participatory and performative aspects of your work changes people and affects them more than doing a painting or something that they view?

Lise: I will try. I decided on embroidery. It wasn’t a method that was present in my work before this project. I wanted the sewing, the repetition and the tactile nature of the project. When you are holding that name, that cloth, that thread, it becomes a presence and it leaves a mark. It plants a seed. You may be more aware when you later encounter similar issues and you may be closer to caring. Every time “Desconocida” is exhibited, I do a performance called “Presence” at the openings. I use my voice to give a loud “Ah” and then go silent, repeating this cycle with variations. The intention is to bring people to the present moment; neither myself or them can escape. Similar to embroidering the names, the performance may bring you closer to yourself and open you to engage with the labels.

Miguel: You’ve mentioned that you have worked on the project for ten years? How long do you intend on continuing the project? I know your answer would probably be “as long as these events keep happening” and a follow up question, do you see this collection eventually being purchased or how would you want it to be archived?

Lise: Initially, I did not plan to work on it for ten years. However, the violence hasn’t stopped, people continue to participate and the project remains alive. To go back to Juárez and México City now 10 years after the project started is significant for the life of the project. After touring the world, it makes sense to return to where it began. I have great hopes it will now tour Mexico and the US.

Eventually, I would like the project to find a permanent home and not end in my studio. Ideally it would be displayed to form a bridge to new types of engagement and activism.

In the meantime, it needs to continue its travel. There are always competing demands on us, and sharing the project sustains our attention to this crucial issue.

Nicolas: This is a two-part question. What messages do you hope to get across to the families that you meet and how do you plan to deal with the trauma in regards to yourself and the viewers and participants of the project?

Lise: I met some of the families in 2007 and 2008 through Marisela Ortíz Rivera, co-founder of the organization “Nuestras Hijas de Regreso a Casa” (The return of our daughters to their homes). I have been in contact with her and with Diana [Washington-Valdez] throughout these ten years. I’m bringing all the embroidered labels to the families as proof of solidarity and care for their struggles. This project can never substitute the work they do. In letting them know that others bare witness, my hope is that this will provide comfort and encourage them in their fight. Moreover, the project´s international character can be used by the local activists to add pressure to their Government. Amnesty International, Mexico are interested in a possible collaboration for the coming year.

Miguel: I think this is a very important project and it needs wider exposure in the United States because the femicides are still occurring. A lot has quieted down but it is still happening on a regular basis.

Lise: When I exhibit the project, I install the labels on the wall in Morse code spelling the Mexican and U.S. anthems. The lyrics are interwoven much like the situation in Juárez is inseparable to the border, in the particular, to the NAFTA agreement and the existence of “Maquiladoras”.

Miguel: Has there been any criticism of the project in your country, have people asked you “Why are you doing this?”

Lise: There have been many asking, “Why are you so involved in something happening in Cd. Juárez?” My answer is that it is not only happening in Juárez. The violence against women happens in every society, whether poor or rich. It is an issue affecting all of us. I remember an embroidery workshop in Tel Aviv and some students asked “Why would we care about what happens in México, when we have enough to deal with here?” But after we embroidered, they said it was good to care. That’s what I believe, even if you start focusing on an issue far away, you begin to see similarities which resonate with your country, city and neighborhood. I want us to ask ourselves how things are where we live.

Miguel: My last question, what do you want people who may hear or read about your project to take away from it?

Lise: I believe this project, in addition to bringing awareness to a horrific situation, also contains hope. There is hope if we get involved. It may sound idealistic but that is what I believe. I trust that art can serve as a critical voice and reach people differently. Like Eleanor Roosevelt stated, “Where after all do universal human rights begin? In small places…close to home…so close and so small that they cannot be seen on any maps of the world.”

I want to add that the Desconocida Unknown Ukjent project is generously supported by the Norwegian Art Council; the Institution Fritt Ord (Freedom of Speech); Norwegian Craft; The Norwegian Artists Association Sponsorship and OCA.

Miguel: Okay, thank you Lise and Harald for this interview.

Nicolas: Thank you.

—

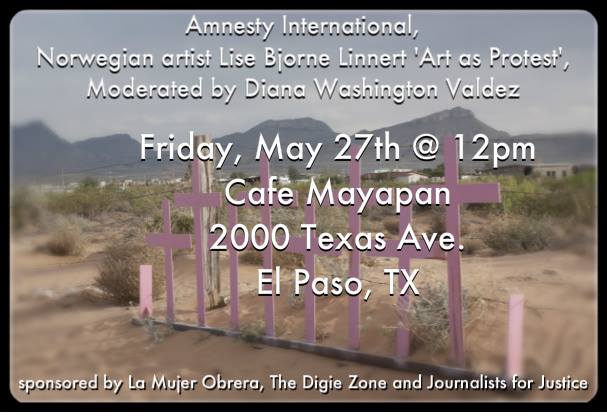

Internationally recognized artist Lise Bjørne Linnert, from Oslo, Norway will be speaking about her project titled Desconocida Unknown Ukjent as part of a panel focusing on “Art as Protest,” that seeks to memorialize victims of violence through art at Café Mayapan in El Paso, Texas on Friday, May 27, 2016 at 12 noon. Other panel members include Margarita Cabrera, renowned artist based in El Paso; Marisela Ortíz, co-founder of Nuestras Hijas a Regreso a Casa who fled threats in Juárez and received U.S. asylum; (tentatively) a member of Mexicanos en Exilio (Mexicans in Exile), and Miguel Juárez, doctoral candidate, arts advocate and activist. Diana Washington-Valdez of Journalists for Justice will be the moderator. The panel is sponsored by The Digie Zone, Journalists for Justice and La Mujer Obrera.

By: Miguel Juárez & Nicolas Silva | Photo Credit: Lise Bjørne Linnert

Miguel Juárez is doctoral candidate in history at the University of Texas at El Paso. His research focuses on cultural issues along the U.S.-Mexico border. You can follow him @miguelJuárez

Nicolas Silva is a multidisciplinary researcher, thinker, writer and artist. He graduated with a Bachelor of Science in Microbiology at UTEP and plans to make science fiction a reality. Follow him @nicodsilva on Twitter or he can be contacted at [email protected]